- Home

- Gibney, Michael

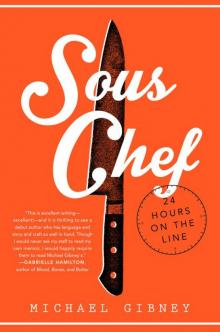

Sous Chef: 24 Hours on the Line

Sous Chef: 24 Hours on the Line Read online

Copyright © 2014 by Michael A. Gibney, Jr.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

BALLANTINE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Gibney, Michael.

Sous chef : 24 hours on the line / Michael Gibney.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-8041-7787-0 (hardback : acid-free paper)—

ISBN 978-0-8041-7788-7 (eBook)

1. Gibney, Michael. 2. Cooks—New York (State)—New York—

Biography. 3. Food service management—New York (State)—New York.

4. Kitchens—New York (State)—New York—Management. I. Title.

TX649.G53A3 2014

641.59’7471—dc23

2014002153

www.ballantinebooks.com

Jacket design: Alex Merto

v3.1

Fyodor Pavlovich, when he heard about this new quality in Smerdyakov, immediately decided that he should be a cook, and sent him to Moscow for training. He spent a few years in training, and came back much changed in appearance. He suddenly became somehow remarkably old, with wrinkles even quite disproportionate to his age, turned sallow, and began to look like a eunuch.

—FYODOR DOSTOYEVSKY, The Brothers Karamazov

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

KITCHEN FLOOR PLAN

KITCHEN CHAIN OF COMMAND

PREFACE

MORNING

ROUNDS

FINESSE JOBS

THE TEAM

PLATS DU JOUR

GETTING THERE

BREAK

SERVICE

MESSAGE

CLOSE

BAR

HOME

MORNING

SELECTED KITCHEN TERMINOLOGY

DEDICATION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

About the Author

KITCHEN FLOOR PLAN

1. Walk-in Freezer 2. Locker Room 3. Chef Office 4. Exit to Loading Dock 5. Curing and Ripening Rooms 6. Pastry Department 7. Walk-in Boxes 8. Dry Storage 9. Meat Roast 10. Fish Roast 11. Cold Side 12. Prep Area 13. Entremetier 14. The Pass 15. Coffee Station 16. Production Storage 17. Dish Area 18. Entrance 19. Exit to Dining Room

KITCHEN CHAIN OF COMMAND

PREFACE

ON A WARM AFTERNOON IN THE SPRING OF 2011, I FOUND myself on a shady corner of Forty-Third Street, just off Times Square, smoking one last cigarette before returning to the twentieth floor of the Condé Nast building to complete the second half of my day clipping magazine articles for The New Yorker’s editorial library—a temporary gig I’d taken between kitchen jobs. I was about to chuck the butt into the gutter when, out of the corner of my eye, I spotted a figure whose large silhouette seemed familiar enough to warrant a second look.

He was a tall man—at least six foot three—with a mange of unattended curls atop his head that made him appear even taller. He stood with his back to me, a navy-blue pin-striped suit hanging loosely over his broad shoulders. He puffed at a cigarette and chatted on his phone, making lively gestures with his free hand while a nimbus of smoke collected in the air around him.

Even though I couldn’t see his face, there was something about his posture that I recognized immediately. He was poised, yet oddly stooped at the same time. His movements were quick and fitful, yet marked by a certain calculated, meditative finesse, which could be detected even in something as simple as the way he flicked the ash from his cigarette.

And then my eyes fell on his shoes and it hit me: checker-print slip-on tennies—with a suit, no less. I knew this man: Chef Marco Pierre White.

I lit up another smoke and waited for him to finish his phone conversation so I could say hello.

Of course, I didn’t actually know the man; I only knew of him. I had read his books and I had seen the hoary BBC clips of him preparing noisette d’agneau avec cervelle de veau en crépinette for Albert Roux while a young Gordon Ramsay traipsed around in the background trying to make his bones. I knew that he was the kitchen’s original “bad boy,” the forerunner of our modern restaurant rock stars. I knew that he was the first British chef (and the youngest at the time—thirty-three) to earn three Michelin stars, and I knew that the culinary world quaked when he decided, at age thirty-eight, to give them all back and hang up his apron. And I knew that in recent years he’d made his way back to the stove, in one form or another, on television and elsewhere. So while I didn’t actually know him, I did know that no matter how gauche it is to descend starstruck upon idols, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to make his acquaintance.

At first, I was met with the annoyance and reservation one comes to expect when approaching celebrities on the streets of Manhattan. I assume he thought I knew him from television. But once I announced that I was a fellow chef, and mentioned the inspiration I drew as a young cook from his books White Heat and Devil in the Kitchen, he let his guard down and we were able to speak casually. Over the course of five or ten minutes, we talked about the craft of cooking, its values and its drawbacks, and what pursuing it professionally does to the body and mind.

Eventually he had to get going, and I had to return to work as well. I concluded the conversation by asking him how he felt about quitting the industry. He paused dramatically and pulled on his smoke.

“No matter how much time you spend away from the kitchen,” he said, “cooking will always keep calling you back.”

We pitched our butts and parted ways.

I was sixteen years old when I started working in restaurants. I managed to land a job washing pots in an Irish pub owned by a high school friend’s father. Half an hour into my first shift, the floor manager swept into the kitchen in search of a dishwasher.

“Hey, you,” he said. “Some kid puked in the foyer. I need you to clean it up.”

It was then that I decided I had to become a cook—if only to avoid vomit detail.

More than thirteen years have passed since I made the decision. In that time, I’ve seen all manner of operation—big and small, beautiful and ugly. I’ve climbed the ladder from dishwasher to chef and cooked all the stations in between. The experiences I’ve had along the way have been some of the best ever and some of the worst imaginable. What follows is my attempt to distill these experiences into a manageable, readable form: a day in the life, as I have seen it.

Within these pages, I’ve compiled material from several different restaurants and several different periods in time. I’ve also sometimes modified the names of people and places. In all instances, I’ve done so in service of authenticity and concision. I don’t presume to offer some judgment of the restaurant business as a whole. I only hope to provide a genuine impression of the industry, to throw its nuances into sharper relief, so that when you, the aspiring cook or the master chef, the regular diner or the enthusiastic voyeur, wish to reflect on the craft of cooking, you can do so from a slightly more mindful perspective. I leave it to you to weigh the virtues and vices.

And now to work.

MORNING

THE KITCHEN IS BEST IN THE MORNING. ALL THE STAINLESS glimmers. Steel pots and pans sit neatly in their places, split evenly between stations. Smallwares are filed away in bains-marie and bus tubs, stacked on Metro racks in families—pepper mills with pepper mills, ring molds with ring molds, and so forth. Columns of buffed white china run the length of the pass on shelves beneath the shiny tabletop. The floors are mopped and dry, the black carpet runne

rs are swept and washed and realigned at right angles. Most of the equipment is turned off, most significantly the intake hoods. Without the clamor of the hoods, quietude swathes the place. The only sounds are the hum of refrigeration, the purr of proofing boxes, the occasional burble of a thermal immersion circulator. The lowboys and fridge-tops are spotless, sterile, rid of the remnants of their tenants. The garbage cans are empty. There is not a crumb anywhere. It smells of nothing.

The place might even seem abandoned if it weren’t for today’s prep lists dangling from the ticket racks above each station—scrawled agendas on POS strips and dupe-pad chits, which the cooks put together at the end of every dinner service. They are the relics of mayhem, wraiths of the heat. In showing us how much everyone needs to get done today, they give us a sense of what happened in here last night. The lists are long; it was busy. The handwriting is urgent, angry, exhausted.

But now everything is still.

On Fridays you get in about 0900. As you make your way through the service entrance, a cool bar of sunlight shines in from the loading dock, lighting your way down the back corridor toward the kitchen. Deliveries have begun to arrive. Basswood crates of produce lie in heaps about the entryway. A film of soil still coats the vegetables. They smell of earth. Fifty-pound bags of granulated sugar and Caputo 00 flour balance precariously on milk crates. Vacuum-packed slabs of meat bulge out of busted cardboard.

You nose around in search of a certain box. In it you find what you desire: Sicilian pistachios, argan oil, Pedro Ximenez vinegar, Brinata cheese. These are the samples you requested from the dry goods purveyor. You take hold of the box, tiptoe past the rest of the deliveries, and head to the office.

The office is a place of refuge, a nest. The lights are always dim inside. It is small, seven by ten feet maybe, but it’s never stiflingly hot like the rest of the kitchen. A dusty computer, its companion printer, and a telephone occupy most of the narrow desk space, while office supplies, Post-it notes, and crusty sheaves of invoice paper take up the rest. Below the desk is a compact refrigerator designated FOR CHEF USE ONLY. It holds safe the chefs’ supply of expensive perishables: rare cheese, white truffles, osetra caviar, bottarga, fine wine, sparkling water, snacks. Sometimes, there’ll be beers in there; in such cases, there’ll also be a cold cache of Gatorade or Pedialyte for re-upping electrolytes. Alongside the refrigerator is the all-purpose drawer, which contains pens and scratch pads, first aid kits, burn spray, ibuprofen, pink bismuth, and deodorant, as well as a generous supply of baby powder and diaper rash ointment, which help keep the chafing at bay and stave off the tinea. At the edge of the desk is the closet, overstuffed with chef whites, black slacks, aprons, clogs, and knife kits. Shelves of cookbooks adorn the walls’ highest reaches, and below them hangs a mosaic of clipboards fitted with inventory sheets, order guides, BEOs, and SOPs. One of the clipboards—the one with your name on it—holds a near infinity of papers. On each sheet is a list of things to do: things to order, things to burn out, people to call, emails to send, menus to study, menus to proofread, menus to write, menus to invent.… You try not to look at your clipboard first thing in the morning.

As the opening sous chef, the first thing you do is check for callouts. In good restaurants, these are rare. A good cook almost never misses a shift. He takes ownership of his work; he takes pride in it. He understands how important he is to the team and he will avoid disappointing his coworkers at all costs. Regardless of runny noses or tummy trouble, regardless of stiff necks or swollen feet, regardless of headaches or toothaches or backaches, regardless of how little sleep he got the night before or what fresh hell his hangover is when he wakes up, a good cook will always show up for work in the morning. But things happen, of course, and sometimes even the most high-minded cooks must call out. And when they do, it’s up to you to find someone to cover for them. Given the limited roster of cooks in most restaurants, this task is often extremely difficult—something of a Gordian knot. So, if the problem exists, it’s important to diagnose it as early as possible.

If there aren’t any callouts, you get a cool, peaceful moment in the shadowy office to take stock. This moment is a rare encounter with tranquillity that must be relished. You chomp on a hunk of the morning’s freshly baked bread and click through your email. You fire up a few eggs over medium, trade morning text messages with your girlfriend. You duck out and smoke some cigarettes on the loading dock, step over to the corner store for a seltzer and a paper. You do as little as possible for as long as you can. For now, for just this very moment, the kitchen is yours.

Eventually your attention turns to the box of samples. It is fully within your purview—in fact it’s your charge—to inspect them for quality. The executive chef has made this clear. He trusts your instincts and expects you to act on them. Nevertheless, an adolescent excitement stirs in you when you open them up.

The Sicilian pistachios, forest green, are soft in your hands, succulent in your mouth. They are rich and sweet, like no nut you’ve had before. You twist the cap on the argan oil and a sumptuous perfume fills the air. Drops of the golden liquid trickle down the neck of the bottle onto your knuckles. Wasting it would be a sin. You lick it off. It is robust, plump, nutty. The PX vinegar counters the sultry fat with a sharp burst of sweetness. Unlike most vinegar, this redolent nectar is thick and syrupy, with layers of flavor.

The Brinata—the queen piece, wrapped in white paper with a pink ribbon—summons you. You gently lay the cheese in the middle of the desk and begin to undress it, slowly peeling away the wrappings to reveal a semihard mound with delicate curves and moon-white skin. To use your fingers would be uncivilized. You trace the tip of a knife across the surface in search of the right place to enter. In one swift motion, you pierce the rind and thrust into its insides. You draw the blade out, plunge in again. You bring the triangle to your lips. It melts when it enters your mouth. Your palate goes prone; gooseflesh stipples your neck.

This is the life, you think.

Afterward, you smoke another cigarette out on the loading dock and ready yourself for the day.

ROUNDS

TIME TO GET CHANGED. YOU RIFFLE THROUGH THE OFFICE closet until you find a freshly pressed coat with your name on it.

Good whites are designed to be comfortable for the long haul—the hot, extended blast. Your coat, fashioned of high-thread-count cotton, buttons up around you like a bespoke suit. Unlike the standard issue line cooks’ poly-blend, the material for the chef’s coat is gentle on the skin, with vents in the armpits to let in air when it gets hot. Your black chef pants, in contrast to the conventional, ever-inflexible “checks,” are woven of lightweight, flame-retardant fabric meant to keep your bottom safe when hot grease splashes and fires flare. They slide on like pajamas. Your shoes, handmade Båstad clogs, conform to your feet like well-worn slippers. They’re ergonomically designed to reduce joint and back pressure, with wooden soles lined with a special rubber that’s engineered to withstand chemical erosion and to defy slippery floors. When properly dressed, you’re clad in custom-fitted, heat-resistant armor that’s light as a feather and comfortable as underwear.

Also in the closet is your knife kit. This kit represents everything you are as a cook and as a chef. Not only does it contain all the tools you need to perform the job, but its contents also demonstrate your level of dedication to the career. Certain items define the most basic kit: a ten- or twelve-inch chef knife, a paring knife, a boning knife. Other additions, though, might indicate to your colleagues that you take your involvement in the industry a little more seriously: fine spoons, a Y peeler, a two-step wine key, cake testers, forceps, scissors, miniature whisks, fish tweezers, fish turners, rubber spatulas, small offset spatulas, a Microplane, a timer, a probe, a ravioli cutter, a wooden spoon.… While these items are typically available for general use in most kitchens, having your own set shows other cooks that you are familiar with advanced techniques and that you know what you need in order to employ them. Also, having such a ki

t at your disposal means that you are ready to cook properly no matter what the circumstances.

Most important, though, your knives themselves tell how much the job of cooking means to you. A dull knife damages food. We are here to enhance food. Extremely sharp knives are essential for this purpose.

No one makes knives better than the Japanese. Every Japanese knife is perfectly balanced to perform a specific function, a specific cut. Its precision in this respect is unrivaled. Its sharpness, too, is unmatched. The metallurgy is most refined, a coalition of hardness and durability. No sophisticated kit lacks Japanese blades.

You take a moment in the office to examine yours, reflecting on your level of dedication. You know these knives as you know your own body. Their warm Pakkawood handles have shrunk and swelled to fit your hands; each blade welcomes your grip the way a familiar pillow welcomes the head at day’s end. You could cut blind with any of them. Their individual features, their nuances, are so entrenched in your muscle memory that even as they sit on the table, you can imagine how each one feels when you hold it.

The nine-inch Yo-Deba is bulky in the hand. She is top-heavy—a bone cutter, built to cleave heads and split joints. Beside her is the seven-inch Garasuki, a triangle of thick metal, meant to lop apart backs and shanks. She’s heavy, too, but more wieldy, with a weight that’s balanced at the hilt. Her shape tapers sharply from a hefty heel to a nimble nose, delivering her load downward to the tip. Honesuki, Garasuki’s miniature sister, sits beside her, similar in shape but lighter and more agile, for dainty work among tendons and ligaments. Even more ladylike is the Petty. Her slim six inches slither precision slits deftly through the littlest crevices. She works tender interiors, snipping viscera from connective tissue. Next to Petty is Gyutou—“Excalibur,” as you like to call her. She is the workhorse of the pack, trotting her ten inches out whenever heaps of mise en place need working through. And at the far end, finest of all, is the slender Sujihiki. At eleven inches she’s the longest of the bunch, but despite her size, she’s the most refined. She’s not built for the brute work of the other blades—she’s made to slice smoothly. A one-sided edge optimizes her performance. While her outward lip traces lines in flesh with surgical exactitude, the convex shape of her inward face attenuates surface tension, releasing the meat. Cuts go slack at her touch; fish bows beside her.

Sous Chef: 24 Hours on the Line

Sous Chef: 24 Hours on the Line